Rae Spoon: Looking for “Friends in Low Places”

“I’m actually struck very hard by the Stampede and how ‘unhinged’ it is. All these posters and every T-shirt on Marketplace — it’s just, ‘Let’s get unhinged!’”

Rae Spoon is speaking over the phone from their former hometown Calgary. Connecting with New Feeling in the weeks preceding the launch of the annual Stampede, they’re beguiled by a new provincialism. “Unhinged” has emerged as an unofficial slogan for the international tourist draw’s storied tradition of all-day liquor service and the volatile environment it can facilitate, and that spirit’s already in the air in town.

“As long as I’m in a car, I’m safe here. If I’m out on the road, that’s when people start throwing things,” says Spoon, who is transgender and non-binary. Their delivery is light and their humour dark, but every joke hides a sliver of truth.

Currently splitting their time between Montreal and Toronto, Spoon marked their prodigal return a day earlier, visiting town for a set and speaking appearances at Sled Island Music and Arts Festival. The occasion also follows Spoon’s return to country music and the genre they began their career in at the beginning of the millennium.

“I bet a lot of people leave their hometowns to make themselves different,” Spoon muses, “but often you find out where you’re from when you leave, you know?”

Spoon explores those complicated circumstances at length in a Substack post that also teases a forthcoming cover (since released) of Garth Brooks’s “Friends in Low Places.”

“I retired from country music in 2007 (to explore other genres) because I did not feel that I (and many of my friends) were safe in the country-music establishment. I was not willing to continue participating in white-centering, ultra-colonial, cis/hetero-centric, spaces that deny the Black and Indigenous Roots of the genre,” Spoon writes.

But today’s cultural field feels like an explosive inversion of the dynamics that prompted the musician/author to put distance between themself and the relatively marginal echo chambers of country music.

Spoon’s return to country music is also inextricably linked to the shifting political climate, both within the genre and the world at large. Spoon is deeply aware of the growing backlash against marginalized communities in both the U.S. and Canada, with chart-toppers like Jason Aldean and Morgan Wallen adopting increasingly hard-right stances. At the same time, Spoon has observed establishment country acts subverting the reactionary environment they were once forged in to defend marginalized people and secure a platform for more diversity.

“I think diversity is the answer to the problems that are here, and the answer to the problems that are coming,” Garth Brooks said in conversation at Billboard Country Live in 2023, announcing the opening of a bar called the Friends in Low Places Bar and Honky-Tonk in Nashville’s South Broadway District and responding to Kid Rock’s transphobic tantrum earlier that year.

Just steps away from Kid Rock’s Big Ass Honky Tonk Rock N’ Roll Steakhouse (from which the country-rap rocker pulled Bud Light after parent company Anheuser-Busch enlisted transgender activist and influencer Dylan Mulvaney as a brand ambassador), Brooks pledged his establishment would be an inclusive space.

“Our thing is this — if you [are let] into this house, love one another. If you’re an asshole, there are plenty of other places on lower Broadway.”

“There has been a shift,” Spoon says, “even in folks you would never think there would be a shift or might’ve served as icons for culture that was very rigid.”

With artists like Beyoncé, Lil Nas X, Orville Peck, and Chappell Roan penetrating the commercial country-music sphere, Spoon sees country music today as an actively diversifying space, but they also worry the genre (and the industry more generally) has been drifting from its proletarian roots for some time.

“If you want to be an artist and you’re working-class, you pretty much have to start doing sort of middle-class drag in some ways,” Spoon observes.

“You’re working off writing grants and things like that. I don’t have a university education,” they add, unpacking their own standpoint. “I was the first person to graduate high school in my family. And I write books now, too.”

Algorithmically amplified via social media, previously fringe reactionary politics increasingly shape mainstream politics in the West, influencing everything from how politicians cater campaign promises to policy implementation.

Weaponizing resentment over economic precarity, Trump’s 2024 campaign rode transphobia into a second presidency (“Harris is for They/Them; Trump is for you”). Upon inauguration, the president promptly criminalized gender-affirming care under the guise of reducing social spending (it won’t), and issued a directive to restrict entry to the U.S. “to require that government-issued identification documents, including passports, visas, and Global Entry cards” reflect a person’s sex “at conception” — easily interpretable as a broader ideological defence against dissenting opinion and progressive social reproduction (the ACLU secured an injunction compelling the State Department to resume issuing passports baring electively updated M, F, or X markers, but it only applies to residents, and its preliminary status makes its future uncertain).

Citing the broad attack on trans rights in the U.S. and U.K., as well as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (Spoon has a compromised immune system related to complications from treatment they received for cervical cancer — and, they correctly point out, COVID could still “take anyone out, actually”) and artistic boycotts like Strike Germany (which Spoon has pledged not to cross out of support for a free Palestine), Spoon says touring new music abroad is off the table for now.

“I can’t go to America anymore, and I’ve been disinvited by [Canadian] universities because I’m trans,” Spoon explains.

“The fascism is not microaggressions at this point. It’s very clear what’s going on.”

With today’s public discourse offering a viral retread of 1970s-style resentment politics (which coincidentally prompted Richard Nixon to invite Merle Haggard to the White House after his team identified the anti-counterculture sentiment fueling “Okie from Muskogie”) what better time to reclaim the terrain of country music’s folk politics?

Recession besetting most Western economies, Garth Brooks delivered “Friends in Low Places” at the end of summer 1990. Putting listeners in the boots of its protagonist — who arrives underdressed at an ex’s wedding, steals the groom’s champagne flute, delivers a toast, and leaves to drink beer and whiskey with friends at a bar — it is a song about defiant class (im)mobility and refuge. Allowing listeners to nimbly navigate the gulf between high and low culture with drink in hand, an electric guitar solo and a fade-out sing-along, it resonated immediately as a blue-collar anthem, propelling Brooks to become the best-selling solo albums artist in the U.S. ahead of Elvis Presley, and second only to the Beatles as recently as last year.

“The whole song takes place in a wedding, which can be very awkward for queer and/or trans people, because there’s so many gendered things playing out,” Spoon says, addressing the coding pageantry of Western marriage ceremonies and the universality of the song’s message. “You don’t even have to be trans or queer to have been made to wear something you didn’t want to to a wedding. It’s very obligatory.”

Spoon assembles a team of trans and non-binary musicians to bring new life to Brooks’s song. Joined by Ky Brooks (engineer – no relation to Garth), Robyn Gray (guitar and synth), Evelyn Charlotte Joe (upright and electric bass), and Heather Kirby (mastering), Spoon’s cover rides balmy synth lines, fried guitar tones, shaker percussion and pronounced sub bass into new low places. Trading Brooks’s original fade-out for a closing bass phrase and swelling synth pads, the arrangement’s murky but quirkily ambiguous punctuation expresses a sense of uncertainty about the future.

The cover is also high on the remembered alienation and temporary liberations of a childhood and adolescence spent in an evangelical Christian Pentecostal family that worked logging and oil-patch jobs. Growing up, Spoon wasn’t allowed to listen to secular music, but they have distinct memories of their uncles invoking the chorus of “Friends in Low Places” like they were memeing in response to different social situations.

“It was a real popular thing to just bust into singing out of nowhere,” Spoon says. “Right up there with ‘Go, Flames, go.’”

While the sing-along outro was perhaps Brooks’s most prescient reading of the populist potential his recording of “Friends in Low Places” would have, in Spoon’s hands, replicating that component may have been redundant. Written in the first person, part of the magic of “Friends in Low Places” is how immediately it can communicate new meaning when its words are embodied by new voices. Written by professional songwriters Earl Bud Lee and Dewayne Blackwell, a version of the song was first released by David Wayne Chamberlain in 1989, but it wouldn’t hit the charts until Brooks recorded his version.

Spoon centres their voice, too, in the slightly modified title of their cover, incorporating the pronoun of the track’s titlesake hook for a more declarative mantra: “I’ve Got Friends in Low Places.”

While international touring is off the table, Spoon still plans to find other transgender country artists abroad to play, write, and record music with as they tour across Canada this summer, encouraging folks in the U.S., U.K,, and Germany to send them their music, zines, and books, to collaborate remotely on music production, and generally catch up online. For Spoon, “I’ve Got Friends in Low Places” is as much a call to comrades as a queered anthem.

The first of more country music to come, Spoon says they opted to release the cover first as a way of easing fans into their new (old) stylistic mode.

“I’m very aware there are audiences [who] might not remember me playing country, because I stopped in 2006/2007,” Spoon says.

“It would feel really out of left field for me to start ripping on the banjo [again],” they continue. Since 2008’s breakthrough Superioryouareinferior, Spoon has developed a more alternative sound, experimenting with electronic beats, textures, and vocal modulation like AutoTune as recently as Not Dead Yet (2023). Aesthetically, the cover bears closer resemblance to those records than early-career output like Throw Some Dirt on Me (2003) and Your Trailer Door (2005).

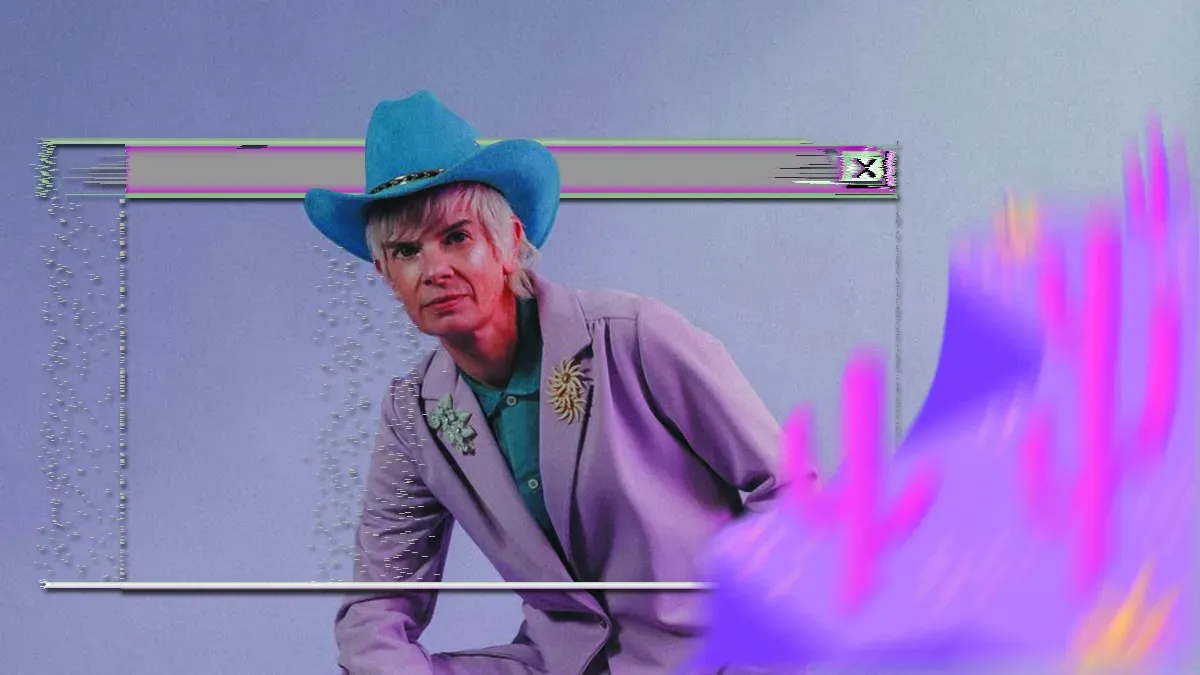

Leaning into the wedding-crasher framing of the song, in the marketing materials for the Brooks cover, Spoon wears drag to subvert a number of wedding stereotypes, and the right-wing’s recentring of cis/hetero nuclear family values with them. Pastels abound in the overall pallette, but the common denominator is lavender — a stated nod to queer country pioneer and vocal Marxist Patrick Haggerty and his band Lavender Country — and with it an acknowledgment of the colour’s importance as a beacon for 2SLGBTQIA communities.

“I consider myself to be middle-aged, so it’s cool to be like, there’s younger generations [than mine] and there’s also elders,” says Spoon, 44. “We can hold all those things together and encourage each other to keep going even when it’s really hard.” An elder millennial who just missed Generation X, the Cold War, and its connotations for political futures abroad, historical continuity is both a responsibility and an opportunity.

“I’d rather have ancestors any day than be the first one. Nobody wants to be the first one of something — and nobody is. That’s starting history over, meaning whoever came before you is erased.”

A press release promises “I’ve Got Friends in Low Places” heralds a new “Hyper Country era,” and Spoon confirms an album sharing the name of the aforementioned period is on its way — they’ll even pick up a banjo again.

As a concept, “hyper country” rings almost paradoxical, simultaneously connoting the flattening online connectivity specific to the cusp of the Web3 version of the information age and a rural immersion more closely defined by raw materials. Beside the reference to country-western music, the other obvious benchmark is hyperpop, but Spoon says the material they’re working on for the release is more spiritually indebted to the genre than it is aesthetically.

“It’s not hyperpop,” Spoon says, but the album is inspired by the genre’s trans roots and will borrow from its experimental, maximalist production ethos and historical tradition of remote collaboration.

“I’m not doing a lot of high voice modulation, yet.”

Produced by fellow Alberta expatriate alaska B (YAMANTAKA // SONIC TITAN) and tentatively slated for release in February 2026, Spoon says to expect a denser expression than “I’ve Got Friends in Low Places,” with more hands playing on the album. In addition to banjo, Spoon promises it will involve an eclectic mix of traditional country-western sounds like mandolin and slide guitars, as well as influences informed by their ongoing long-distance collaborations with trans and non-binary artists working across genres like jazz, metal, and other experimental music.

The album will also tackle themes of disability justice, trans identity, and the experiences of marginalized communities, especially in relation to country music’s often exclusionary history. Spoon hopes the album will create space for the stories of marginalized people, including trans, non-binary, and disabled artists that are often silenced in mainstream country music. It won’t be a protest album, they say, but it will offer a vision for a future country music that is diverse, inclusive, and radical.

“It’ll be interesting to see what’s next for it, but I think there are lots of disabled people who can’t leave their houses, and trans people — we don’t leave our houses unless we have to. Because it’s bad outside! So I think that’ll continue.”

As the world around them grows more unhinged, Spoon’s return to country offers a glimpse into a future where the genre can evolve to include those it once sought to exclude — and where the energy of the times might just be the fuel for something more inclusive and revolutionary.

“It’s about keeping our tanks full — apologies for the Alberta metaphor.”

Full disclosure: Publicity for Rae Spoon’s cover of “Friends in Low Places” was managed by Take Aim Media. New Feeling board member Paul Brooks is the CEO and Director of Publicity at Take Aim, but Spoon is not his client. Further, board members have no involvement or influence in the decisions made by New Feeling’s editorial working group.

Read more

Sentries: Multifaceted Noise Rock

Step Into Little Stone Crow's World