Always Dreaming: On Diamond Jubilee and Hauntology

There is a spectre haunting Cindy Lee.

Her ghostly album Diamond Jubilee, among the major musical works of the 21st century, is bound up with the past.

Cindy Lee’s compositions are fiddly little slices of heaven. She writes pop songs about memory and loss, sung in a delicate falsetto, backed by sweet harmonies. These reveries are at once soft and harsh, rendered with guitars that twang and distort and high frequencies that could have been EQed out but instead cut through sharply.

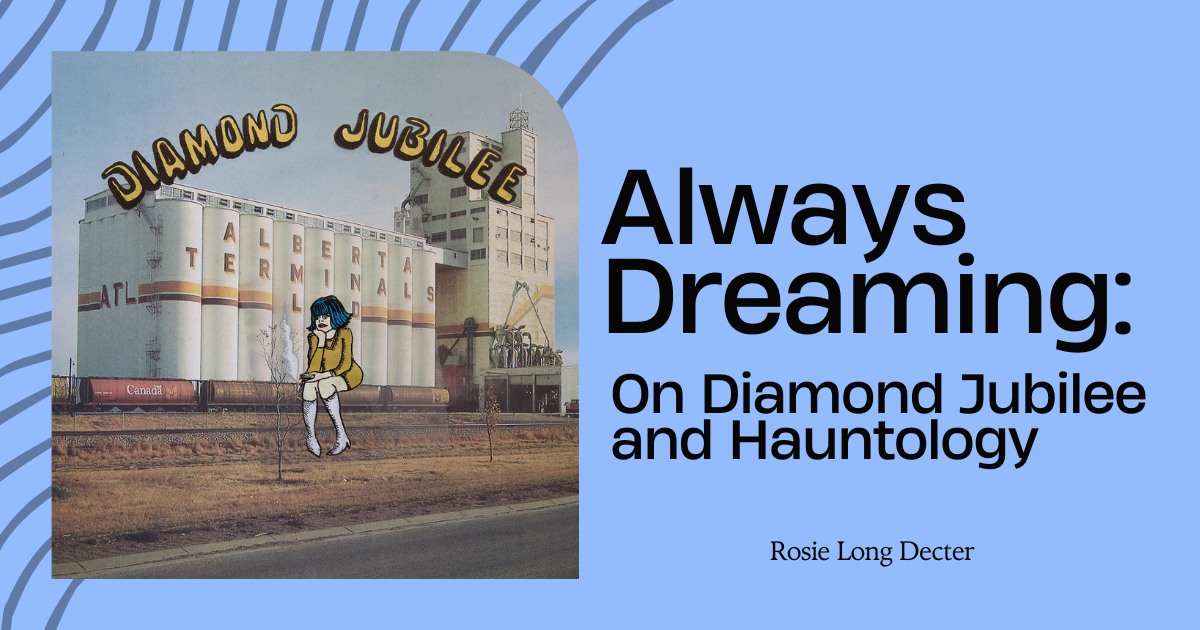

On the album cover, Cindy Lee sits in cartoon form in front of an Alberta grain elevator, head in her hand, looking like a girl who knows she needs to get somewhere better.

The album was met with rapturous acclaim upon its March 2024 release, the kind of buzz that rarely builds outside of a viral TikTok these days. Critics and fans described it as haunting; Ian Cohen, in a meta-review for Stereogum – “At the Cindy Lee Show, Making Sense of the Hype” – off-handedly called it hauntological, employing the term without unpacking what it might mean for Miss Lee.

What is she haunted by? Or, who is she haunting?

In his 2014 book Ghosts of My Past, the late cultural critic Mark Fisher diagnosed a temporal problem in contemporary music. For Fisher, there was a clear lack of innovation in the popular music of the 21st century, evincing a cultural failure – or, even worse, an inability – to meet the political moment.

During what he calls the popular modernism of the ’60s through the ’90s, Fisher argues, new genres emerged at a rapid pace in pop music. Punk, new wave, hip-hop, house, techno, jungle, and all their musical relatives, emerged as modernist aesthetic representations of particular sociopolitical situations, whether that situation was the razing of Black and brown neighbourhoods in New York City, the collapse of the auto industry in Detroit, or Thatcherite dispossession of the English working class.

“It was through the mutations of popular music that many of those of us who grew up in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s learned to measure the passage of cultural time,” Fisher writes. “But faced with 21st-century music, it is the very sense of future shock which has disappeared.”

Instead, contemporary music – Arctic Monkeys and Adele are two of Fisher’s chief examples – is made using the styles of the past and the recording techniques of the present. These artists “belong neither to the present nor to the past but to some implied ‘timeless’ era, an eternal 1960s or an eternal 80s.”

Rather than explicit nostalgia fodder, then, contemporary music naturalizes a sense of inertia. There is no future, no impulse towards innovation, only an endless recycling of anachronistic forms, severed from the sociohistorical contexts in which they emerged.

Hauntological music, on the other hand, refers back to those contexts. It is steeped in the sonics of decay, bringing up the past to emphasize its disintegration.

“Think of hauntology as the agency of the virtual,” Fisher writes.

Hauntological music, Fisher argues, bears the markings of what has been lost in the transition to neoliberal capitalism.

Fisher distinguishes hauntology from a reactionary or colonial nostalgia for the post-war social order, an order that relied on the exclusion and oppression of a great many peoples. His point is not that things were altogether better in the ’70s, but that there’s been an excavation of cultural activity and imagination, scooped out by neoliberal social arrangements.

“We shouldn’t have to choose between, say, the internet and social security,” Fisher writes. “What haunts is the spectre of a world in which all the marvels of communicative technology could be combined with a sense of solidarity much stronger than anything social democracy could muster.”

Hauntological music – the disintegrating tape loops of William Basinski, the digital-analogue apparitions of Boards of Canada – is music that, instead of naturalizing the past, materializes it. Hauntology is a state of failed mourning, of refusing to get with the program. Hauntology dwells in the what could have been.

“In the diamond’s eye / shining down on me, a single memory / and it’s of you,” Cindy sings, opening Diamond Jubilee alongside a resolute strum.

Cindy Lee is the persona of Pat Flegel, previously of the Calgary cult post-punk group Women. On Diamond Jubilee, Flegel doesn’t tell stories, exactly. The narrative that unfolds across the record is more like a series of scenes, some specific, some vague. Flegel’s lyrics are often difficult to make out amidst the reverb and distortion, but a few motifs recur. Cindy in the moonlight. Cindy missing some place or person. Cindy on her way somewhere else.

“I can’t turn back / I’m always dreaming,” she sings. Cindy is haunted by old lovers and friends, visions of pleasure gone. She knows she can’t return, but the past hangs around anyway. Memory shines on her.

The specifics paint a picture of Cindy as a vagabond. She’s on a greyhound, heading to New York. She’s dreaming of a lover in Dallas. She’s moving out west, living off government money – a cheque, to be clear. No direct deposit for Cindy.

Cindy is a diva, glamorous and gritty. But is she real? Or just a recollection?

Diamond Jubilee sounds like a dream, half-drenched in reverb, half fuzzed and fritzing. It manifests, as many have noted, like a radio signal that’s only partially coming through. Or, like a discarded studio recording from another time.

“Wild Rose,” for example, has the feel of a live off the floor studio session. There’s a looseness to the performances, like a band that kept playing once they thought the mics were turned off, and maybe half of them were. We hear Cindy vocalizing, but it doesn’t sound like she’s singing directly into a mic of her own – it sounds like an accident, a clandestine take.

Cindy herself seems to reach us as a memory, only half-intelligible. Her voice is often quiet in the mix and surrounded by haze, creating a sense of distance that’s both spatial and temporal. “I only wanted to be heard,” she sings on “If You Hear Me Crying,” and you almost want to crane your neck to get closer to the sound.

Songs end and begin abruptly, like someone has changed a channel or flipped a switch, pressing play on another Cindy dispatch. We know that by the time Cindy’s stories have reached us, they have already happened.

(That distance, of course, doesn’t mean the songs don’t hit hard – on the contrary, the album’s fog makes the sentiment all the more potent, melancholic in both substance and style).

Fisher writes that hauntological music breaks the illusion of presence, forcing us to contend with a period of time other than our own. It does this by drawing our attention to audibly outdated recording techniques like vinyl crackle, hauntology’s primary motif. “Crackle makes us aware that we are listening to a time that is out of joint.”

Diamond Jubilee is full of these kinds of markers, sonic dust that emphasizes its recorded nature. A low crackle on “Baby Blue,” mic feedback on “Dallas.” On “Don’t Tell Me I’m Wrong,” the bass sounds dull and honestly, like it’s farting, drawing the listener’s attention to all the frequencies that are missing – all the ways in which Diamond Jubilee sounds wrong.

Flegel’s lyrical choices – naming songs after government cheques and discotheques – further situate Cindy as separate from our era. A diamond jubilee is the celebration of a sixtieth anniversary, typically that of a monarch. Did Cindy record these songs sixty years ago, and bury them in some space-time capsule?

Cindy, singing to us from an oblique past, calls up the memory of pre-neoliberal social organization. This is perhaps clearest in the album art itself: cartoon Cindy sits in front of an Alberta Terminals Limited grain elevator, one that’s still operational in Lethbridge, Alberta, today.

Grain elevators are symbols of Prairie identity and, by extension, Canadian colonialism. Scholar Darin Barney describes them as “as the media through which Prairie social, political and economic life was organized and carried out.” A crucial instrument in the development of Western Canadian prosperity, grain elevators also acted as social hubs and jumping off points for political organization, in the form of cooperatively-owned wheat pools.

With the transition to neoliberal capitalism, thousands of grain elevators were demolished by the companies that owned them, as grain production became concentrated in three multinational corporations. When the elevators were shut down, rail lines to surrounding communities were discontinued, leading to the death of a certain kind of settler Canadian life.

Cindy poses in front of an elevator that is now owned by one of those three multinationals and has been scaled up and renovated for the new era of grain transport. It still bears the logo of the state corporation, Alberta Terminals Limited, that built it in 1932. Like Cindy’s music, it’s both of our time and a formal reminder of what came before.

Everything I have described above is generally agreed upon by listeners: the record sounds like an alien radio transmission beamed in from the past.

But when it comes to determining which specific past Cindy is from, interpretations vary.

“This vast collection of songs feels like a time capsule of long lost recordings of 60s sunshine pop packed full of fuzzy whimsy,” suggests Bandcamp user /mu/coreapologist.

“It’s like listening to the 50s/60s/70s all at once, with a modern filter,” adds loftaurasa.

“This album makes me feel like I’m in 1990 with a head full of drugs and dreams,” writes ejustin.

Ian Cohen in Stereogum, meanwhile, says the album most reminds him of 2011, the year hypnagogic pop by Ariel Pink and James Ferraro was in vogue.

For my part, I hear snippets of my favourite ’60s songs. The guitar strum from “Proud Mary” on “Diamond Jubilee;” the rumbling percussion of “Always Something There To Remind Me” on “Kingdom Come.”

Diamond Jubilee has something from each of these eras. There’s the spindly guitar-work of ’50s country; the spacious harmonies of ’60s girl groups; the after-hours grime of ’70s post-punk; the sweet chord progressions of ’80s indie pop; the tinny squeals of ’90s DIY; and, definitely, the ambient haze of 2010s hypnagogia.

Jubilee reworks these elements into an elegiac masterpiece, a two-hour plus ode to drifting across the continent, and the people and places recalled along the way.

By dabbling in each of these periods, Flegel also provides a crash course in the history of rock. Jubilee calls up a roughly 60-year period of popular music: from the emergence of rock as a dominant musical genre in the ’50s and ’60s, to the 2000s indie boom of the blog era and the iPod.

Flegel merges stylistic conventions from previous decades with a recording style that conveys decay – a sense that these conventions are fraying at the seams, that the recording might degrade beyond recognizability.

This approach suggests a decomposing of rock music itself; the genre’s halcyon days can be approximated, but only in a lo-fi form. Diamond Jubilee brings to mind the innovations of each era, the humming sense that something new was around the corner, at the same time as it sounds like that hum has already corroded.

“In hauntological music there is an implicit acknowledgement that the hopes created by postwar electronica or by the euphoric dance music of the 1990s have evaporated,” Fisher writes. “Not only has the future not arrived, it no longer seems possible.”

Diamond Jubilee is, similarly, haunted by hopes eroded under neoliberalism: a vision of rural settler Alberta, capable of controlling its own means production; a vision of rock music as a disruptive and popular counter-cultural force, capable of resisting corporate control.

Of course, rock has been dead for a long time.

Every generation within that 60-year period has declared the death of the guitar-based, blues-edged genre, as its heroes were subsumed into the upper echelons of wealth and fame or lost to addiction and an exploitative industry. And like the vision of a settler Prairie prosperity, rock’s popularity has always been built on dispossession and exploitation.

At the same time, rock’s foundational myths – rock as sonic disruptor, misfit salve, holding together a host of alternative ways of being – have persisted, as new scenes have emerged to take up the underground torch.

But the disappearance of the conditions that led to the emergence of popular modernism – cheap rent, stable jobs, strong social security, and, let me say again, cheap rent – have made it harder for new freaks to emerge and innovate, to take over empty warehouses and start their own labels and reclaim rock from corporate pincers.

The precaritization of the labour market combined with a housing crisis means that artists are more focused on piecing together enough gigs to pay rent or taking their landlord to court than developing their craft and hanging out with other weirdos. (As I write this, several of my musician friends are on strike at Canada Post, trying to prevent their employer from degrading the company’s union jobs into part-time gig work).

The restructuring of the music industry in the 21st century, meanwhile, has gutted rock’s middle class. The market dominance of streaming platforms and the corporatization of the Internet have led to an over-saturated, algorithm-organized music landscape where even the major labels don’t know how to reach audiences, while recorded music royalties are slim and touring costs sky high. Those conditions foreclose dreams of building a sustainable career in popular music – let alone building a career and resisting corporate logics.

On Diamond Jubilee, though, the mythos of rock music echoes through whatever era you happen to hear.

What Jubilee doesn’t sound like is the present.

Today’s indie rock is dominated by sleek hi-fi production and leans into intimacy. Popular recording techniques like whispered, double-tracked vocals create the sense of an artist who is hanging out in your ear, meant to be carried around with you on your daily routines, adapted to your schedule. Flegel inverts that relation, inviting you to imagine Cindy’s world.

Diamond Jubilee refuses the seamlessness of digital editing. Parts slip in and out of time, you can hear Flegel skip a note or drop a beat. In his otherwise positive Needle Drop review, popular critic Anthony Fantano calls this technical “messiness” – like drums and guitars that are out of sync, or a guitar tone that is “just too shrill” – a shortcoming of the album.

But that unrefined quality gives Diamond Jubilee its idiosyncrasy. The album resists received wisdom about how indie rock, and pop more generally, is supposed to sound right now: smooth, flattened out, easily broken up into bites that feed the algorithm.

It also resists the logic of how indie albums are meant to be released. Flegel initially dropped Diamond Jubilee as a single YouTube stream and a Geocities download, keeping it off the major streamers for many months. In a previous interview, he urged musicians to take a similar distribution approach. “I think everyone should take their music off streaming platforms. Not even strike, just take it off. They’re begging for a penny a play, and it’s pitiful.”

Flegel did no interviews for Diamond Jubilee. In a landscape where emerging artists feel like they have to share Spotify graphics and post endless TikToks lip syncing to their songs, Flegel’s approach to the industry is almost taboo, the return of the repressed: he’s doing what many want to do but feel they can’t.

All those factors, together: the sonic idiosyncrasy, the sublime songwriting, and the outsider release, generated distortion-levels of buzz for a record designed to avoid exactly that.

The rapturous reception of Diamond Jubilee prompted thinkpieces galore, asking if we were seeing cracks in the streaming model of music consumption.

At the time of its release I wrote that the album seemed to have people excited that there might, actually, be another way of doing things: a version of indie rock that can exist outside Spotify, that can sound fucked up and rough, that can run for two hours with no concern about listener attention spans. Indie rock that can be both alternative and popular. (I wrote that before Flegel cancelled Cindy Lee’s tour dates, stepping back from the hype altogether.)

But rather than demonstrating a new path, I think Diamond Jubilee really serves as a reminder of roads previously taken.

Everything about Diamond Jubilee’s release recalled the indie rock heyday of the 2000s, when Pitchfork raves catapulted the careers of Canadian artists like Broken Social Scene and Fucked Up. The indie ecosystem grew around and through the success of those artists – without breakouts who build enduring careers, it’s not possible for indie companies to get their start, and vice versa.

Pat Flegel established his music career during that heyday; his path is not replicable for artists who don’t already have that cred.

For Stereogum’s Cohen, the album’s reception was a near-copy of the kinds of things writers said about previous indie boom acts. “It’s still possible for a band to get heard, given enough talent and perseverance, without a PR agency or a label,” he quotes from a 2005 Pitchfork review of Clap Your Hands Say Yeah. “Damn, maybe this is how it’s supposed to work!”

Cohen suggests that the major change since 2005 is that publications like Pitchfork are no longer the tastemakers. Instead, forum sites like Rate Your Music now have the power to propel bands out of nowhere. Cohen is writing from a critic’s perspective, but he misses that the music ecosystem into which those bands are now launched is completely different.

Corporate subsumption is the starting point for contemporary artists. Nearly everything you share online is always already generating value for a conglomerate. Bands are brands from day one, navigating an Internet ecosystem where music promotes the self, not the other way around. Streaming services (or at least the biggest one) actively promote music that will reduce their royalty payouts.

The internet isn’t everything – there are still local scenes, still DIY tape runs and community radio stations – but across the board, it’s harder to make a living and sustain space for an artistic life.

The “success” of Diamond Jubilee doesn’t prove that there’s a future outside that logic for emerging artists.

If the album itself is haunted by the promises of Prairie rurality and counter-cultural rock, the album’s reception is haunted by the collapse of the indie rock economy. It’s a reminder of futures lost.

What the reception did prove is a desire for other modes of creation and consumption. A hunger that can be accessed, when the stars lineup right.

2024 provided a few other glimmers of inspiring activity in popular music: the SXSW boycott, which forced the major music festival to drop its army sponsorship amidst a U.S.-backed genocide in Palestine. The launch of new music organizations, like the cooperative platform Subvert. The refusal of newly-minted pop icon Chappell Roan to be brow-beaten into presidential endorsement. Glimmers, but they cast a certain light nonetheless.

I’m not as concerned as Fisher about the inability to create the “new.” Some days I feel like there’s nothing exciting under the sun, and some days I hear a new track by Yeule or ASKO and I’m reminded that there’s plenty to be imagined.

What’s more concerning to me, which I think Fisher correctly identifies, is a “destranging” of contemporary music cultures. Fisher writes that contemporary popular music lacks an identification with the alien and aspires instead towards ordinariness.

There is a cultural obsession, I think, with relatability: seeing every artifact through the prism of how it refers back to your own experiences, rather than for how it can bring you closer to the world.

That emphasis on relatability works to uplift cultural texts that speak to the world as-it-is, rather than the world as-it-could-be.

“Identifying with the alien – not so much speaking for the alien as letting the alien speak through you – was what gave 20th century popular music much of its political charge,” Fisher writes.

Diamond Jubilee evinces an alien sensibility: lyrics that chronicle the journey of an outsider, music that reaches for the angelic. As much as Jubilee is bound up in the past, that otherworldly quality gives it a ripple of futurity.

Like on the late album cut “What’s It Going To Take.” The song is a slow ballad, beginning with just voice and strummed guitar. Flegel’s voice is low and upfront, as Cindy sings: “it’s never too late / to get over.” A background vocal echoes her, noting the passing time (“two o’clock / four o’clock / sunrise / sunshine”).

Eventually, Flegel’s lead vocal drops away and a screeching guitar enters with bass and then drums. Fluttering bird sounds dapple the edge of the mix. The background vocal comes back in, shimmering like a vision in front of closed eyelids.

It sounds like Cindy is promising a tomorrow – something almost familiar, and yet strange and unplaceable, on the horizon in your mind.

Read more

Sentries: Multifaceted Noise Rock

Step Into Little Stone Crow's World